This is the first boat I built (age 7). As you can clearly see, it floated, and it was a chick magnet.

This is the second boat. My future wife, Mary Lou, and I came down, on weekends, to Newport Beach from Occidental College and built this 20’ molded plywood Highlander. It was very, very fast.

When we married, and had a couple of young kids, we wanted to sail, but then there were only two kinds of sailboats. Light, trailerable open boats like the Highlander, and heavy, mostly wooden, keel boats that had accommodations, and had to be kept in the water.

The first were easily capsized, and had no accomodations. The second types had to be stored in the water, and unable to sail anywhere except their local areas. To make matters worse, in-the-water slips were very hard to find, and very expensive. These boats, unfortunately, could sink if damaged.

Nether of these were suitable for a family with kids. We solved the problem with a lightweight , trailerable, non-capsizable, unsinkable boat, with cruising accommodations. The secret was a retractable keel, allowing trailering to any desirable sailing area, anywhere, reducing of the risk of capsizing, and eliminating the cost of in-the-water storage. The boats could easily be stored at the owner's driveway or backyard, or in relatively low cost dry storage near a launch ramp.

The fact that these boats were sometimes half the price of the nearest competitors also helped a lot.

Also, there was the monstrous fact that most of the existing old wooden boats were rotting away, and almost all demanded replacement.

Another factor that contributed to the surge in boatbuilding: Unlike plywood and wood planks, fiberglass could create incredibly complex curved surfaces, providing the designer with complete freedom regarding styling. The new fiberglass boats were far better looking than the wooden boats that they replaced.

Faced with the above facts, we saw a huge marketing opportunity.

As a student at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, I started up a major class project. I designed the business that would build on this marketing opportunity. I designed the product, the marketing system, and the financial system. I received lots of A grades for the effort.

At graduation from , the boat and business design project was complete, and off we went.

It costs a pile of money to fire up a business. So, I went to work for Ford to build up a good financial position.

We started immediately after graduation from Stanford to build tooling (in our garage). After a year of hard work, while still working for Ford, we started to produce the boats. After our small business was running like a Swiss watch, (with 30 employees), making some money, and setting up a dealer system to sell the boats, I quit Ford and we went at the boat business full blast, following the exact details of the plan created at Stanford.

The results were spectacular. The results, over the next 50 years, we built over 40,000 sailboats.

Most major sailboat companies were soon to have had a shot at making trailerables, including such well known names as Islander, Columbia, Cal, O'day, Clipper, Coastal Recreation, Newport Boats, San Juan, Ericson, Bayliner, Reinell, Laguna, Olson, Schock and many others. They are either gone completely, no longer attempt to compete in this market, or are building so few of this type of boat that they are no longer a significant factor.

Most of the other builders rented their buildings. Early in the game we bought 5 acres of land and, in 1968, started to build the buildings that our production operation required.

From that time, on the value of land and buildings in our area went through the roof. We benefited from the massive increase in market value of our property, while the competitors saw only the misery of rent increases resulting from the increase in the value of their landlords’ property.

DESIGN PROCESS

All of our design work was done within the company. We did rely on naval architects to help us with complex structural calculations. I’ve attached a drawing of our rather powerful computers and a giant 41" screen that enable us to create digital images of every single part on the boat. These computer images were sent to computer control milling machines that provided all of the cross-sections we needed to create the plugs. (Plugs were wooden and fiberglass mockups over which the fiberglass molds were laid.)

Computer design enabled us to hold remarkably tight tolerances, and easily experiment with alternative design ideas.

These computers saved us hours of time and a lot of money.

CREATION OF THE FIBERGLASS STRUCTURES

All the fiberglass parts, such as hulls, decks, interior fiberglass liners (forming the bunks and tanks), rudders, centerboards and hatches were built in highly polished molds, that had been created by laying up heavy fiberglass shells up over a precise and highly polished wooden and fiberglass mockup of each part. The 65 hull mold is shown below.

During the evening shift, the trailerable boat molds were sprayed with colored or white polyester gelcoat. The gel coat gave the highly polished outside finish, matching the polished finish of the mold.

The white or color coat was then covered with a very thin layer of black gel coat, making it possible to see any air bubbles or voids in the laminate as the layup process continued..

The gelcoat was allowed to cure overnight.

During the day shift, a small crew laid out the layers of fiberglass and polyester resin for the parts. The beauty of this process was that we could vary thickness and material content to account for the high loads placed on any location.

I show photographs of the three materials were used to make up most of our boats.

The fiberglass mat was a relatively thick network of 2 inch long fiberglass strands that were placed in random directions, and held together with a resin soluble binder resin. When saturated with wet polyester resin, fiberglass mat provided bulk, thickness and rigidity.

The fiberglass roving is a weave of strong fiberglass strands provided amazing strength and relatively light weight.

The light weight fiberglass cloth provided a degree of strength, and made for nice smooth surfaces that were visible inside the interior liners.

The pre-cut layers of fiberglass were placed into the molds, one layer at a time.

The fiberglass was then wet out with catalyzed polyester resin using an airless spray system. Rubber squeeges were used to force the resin into the fiberlglass and eliminate air pockets.

Reinforcing stringers and liners were then bonded in to the newly laid up hull or deck.

This is a picture of the 65 hull and its stringers. this is just before the internal liners are bonded in.

Layup for the high production volume trailerable boats was completed early in the first shift and allowed to cure until the night crew came in. They used electric hoists to separate the parts from their molds. They then polished out the mold and applied the gelcoat for the next boat as described above.

For the trailerable boats, one complete set of molds produced one boat per day. At five boats per day, we had five separate sets of molds for peak production..

Here is a picture of one of our trailerable boat decks being removed from its mold'

The following picture shows a deck, interior liners and a hull still in the hull mold..

Here is a 26 hull coming out of its mold.

ASSEMBLY PROCESS

One of the reasons that we sold so many boats is that we were able to keep our costs low.

As a kid, I had some serious education relating to manufacturing. My dad was a salesman for an oil company, selling lubricants to industrial customers. He frequently took me along on his routes throughout Ohio and Pennsylvania. I was exposed to every possible kind of manufacturing system. For building a manufacturing business, this background was better than college.

Henry Ford created the first real production line and built over 20 million of the model T’s at amazingly low cost.

When I worked for Ford, I spent a lot of time examining Henry Ford’s original concept of a production line and watched the various automobile assembly plants improve their production lines into amazingly efficient masterpieces.

What we did was create a long string of highly specialized workstations, through which the boats moved. Each station had all of its tools, jigs and fixtures, parts, diagrams, and samples to show how the station works. With a system like this, we could take a relatively low skill level worker and convert him, within hours, into the world’s top expert at a very limited set of tasks.

As a sidelight, when we were designing a workstation to install deck hardware, we brought in a totally unskilled young guy and presented him with what we thought was finished and perfect workstation. Without further instructions, we turned him loose to see what happened. As it turned out, everything was done perfectly except that the cleats were bolted on upside down. With that enlightening event in mind, we subsequently designed each workstation with visual samples of what the end item should look like.

At peak production, the trailerable boats moved through each station every two hours.

Most of the other builders had highly paid groups of workers that were capable of building the entire boat, and they would move from boat to boat taking with them their tools, parts, instructions,etc. As you might expect, they demanded much higher pay, required much longer training times, and were more likely to make mistakes.

We spent a lot of time and effort to create jigs and fixtures that would make each job fast, easy, and remarkably accurate.

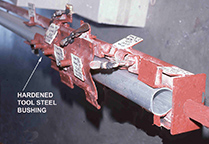

A carefully thought out mast drilling fixture is shown here.

The raw mast aluminum extrusion was clamped in place in the jig, and the three sizes of holes were drilled in a matter of minutes. We never had an improperly drilled hole. The mast was removed from the jig, and the worker assembled the complete mast in a matter of minutes.

The drilling of a large part, such as a deck, required much larger jig. To make the jig, we laid up a lightweight fiberglass shells over a deck. We called these shells “splashes”. We bonded to the splash all of the drill bushings for all of the holes that the deck required.

In the areas of windows and hatch cutouts, we thickened up the splash so that we could drive a roller mounted router around the edges to make exact cuts for the hatches and windows. I don’t think we ever made a bad cut, or had a misplaced hole, even in the thousands of boats that we built.

Efficient jigs like this were provided for every single part that we built.

When the deck came into the drilling station, the splashes were lowered onto the deck, the holes were drilled, accurately. The deck was then moved on to the next station, where a small crew bolted on all of the hardware.

An amazing number of companies failed to provide significant tooling such as this. Their highly paid assembly guys rolled out the drawings on the deck, measured with a tape measure where all the holes were located, and what size drill would be needed. Even with the most brilliant and highly paid worker, mistakes were common, and costs were high.

We spent a lot of time making sure that our tooling was idiot proof. With all of this tooling, our costs were less than half of the cost of competing boats, and we turned out more perfect parts.

COMPUTERS AND AUTOMATION

Like most companies, we made a good start on automation. A big step for us was to purchase an automated milling machine, run by a computer, that cut out all of our wood parts, reinforcements, and a lot of the fiberglass parts. It did the job of 3 workers. It was able to cut out very complex 3D parts of virtually any shape.

EMPHASIS ON PURCHASING

Another major reason that we are able to sell boats at prices far lower than our competitors is that we concentrated on purchasing. Approximately 70% of the cost of a sailboat involves payments to suppliers for parts and materials. In most companies, the purchasing agent is moved up from clerical tasks, because the purchasing job doesn’t look that complicated. (After all, everyone buys stuff, and everyone thinks they are an expert at it.)

Realizing how important purchasing was in the cost of the boats, we spent a lot of time effort and money to attract purchasing geniuses and fully understand what they were buying, and how to buy.. We insisted on having no less than four quotations for everything that we bought. There is nothing better than competition among suppliers to assure that we obtained the lowest possible prices.

We searched the world over for the best suppliers.

While I was at Stanford business school, in addition to designing the boat business, I concentrated and literally majored in purchasing and subcontracting. Most business schools concentrate heavily on sales and marketing. Purchasing gets very little attention. Almost no one, professors, students or otherwise gave much thought to purchasing, and the techniques required for getting the best possible parts and materials at the best possible prices. Negotiating prices and developing supplier competition required a lot of skill, we made the most of it.

DELIVERY OF THE BOAT TO THE CUSTOMER

Getting the boat out the shop doors one thing, but that it had to get to the customer, and this was often expensive. We, like the other builders, initially relied on commercial trucking companies to carry our boats throughout the country. After spending a lot of money on transportation, we began to take on the task of using our own vehicles to deliver the boats.

Happily, my father-in-law was a truck salesman for a major truck manufacturer.. With his help we designed a rather unique boat moving rig that involved a long bed, heavy pickup truck that held two boats, one on top of the other, and a trailer that also held two boats. I’ve attached a photograph of the typical rig, we had more than a dozen of these rigs carried boats everywhere on the continent. The retracting keels made it easy to stack one boat on top of the other and still meet bridge clearance requirements.

We had many of these.

Here's our really big forklift loading one of our trucks.

In addition, we were able to get two boats into a standard large shipping container. This was a very economical way to send the boats overseas.

We also experimented for a few years with shipping boats by rail, on large auto carrier railcars, to the eastern seaboard, where they were distributed to our dealers on their own trailers.

The MacGregor 65 presented more of a shipping problem. We sold these boats all over the world. Many were picked up at our local harbor, Newport Beach, and sailed, literally, to the far ends of the earth. Within this continent, the boats were shipped by truck.

Many of the boats we sent overseas as deck cargo on container ships. It made fort some real adventure. We would launch the boat at a Newport shipyard. I would power the boat to the giant Los Angeles harbor and tie it up alongside the ship that would carry it. The day before, our production crew took a prebuilt steel cradle that was picked up by the ship’s cranes and firmly secured to the deck of the ship. I would generally spend the night on the boat, and in the morning, the boat’s big cranes would pick it up and attach it firmly to the cradle. It was cumbersome and expensive, but we never had a problem with any yacht getting safely to its destination.

The following is one of our 65 is being lifted up on one of the ships

MARKETING

We sold the boats are a large network of dealers, throughout the United States Canada and the rest of the world. They were my business partners and friends.

We also spent a lot of time and effort on informative brochures for each boat, and they were superior to any publication created by our competitors. Copies of all the brochures are shown in this website.

We pulled off one rather remarkable marketing scheme. All the builders claimed they had the fastest boats, and it was not easy to prove they were wrong. We fixed that quickly. We announced to the world that we would put on a big race for all trailerable sailboats that were in production,. by any builder, and we would provide a trip to Tahiti to the winner. We advertised the challenge heavily, and it was a smash success.

The race was won by one of our 21s owned by an excellent sailor named Les Bartlett. He got the free trip, and we had a lot of fun. This forever put to bed the issue of who built the fastest boat. See the brochure for the 21. The beautiful red 21 on the cover of the brochure was Les Bartlett’s boat.

THE DURABILITY OF FIBERGLASS

Steel and aluminum are subject to electrolysis, and corrode away rapidly. Wood rots away like crazy and is eaten by a variety of tiny waterborne creatures, and the hundreds of joints between panels eventually leak, a lot.

Fiberglass, on the other hand, seems to have unlimited life, and solves all of these problems.

Nothing makes me happier than having a customer bring a 20-year-old boat back to the plant, looking as perfect as it did when I came off the assembly line.

This is swell for the boat’s owners, but creates some difficulties for the boatbuilders. Unlike automobiles that rust away to junk within a decade or so, the fiberglass boats remain out there, in great shape. And there is virtually no market for replacement products. For every new boat produced by the fiberglass boatbuilders, a whole bunch are sold on the used boat market. We are victims of our own success. Our toughest competitors were the boats we have built in the past.

We have always made a real effort to make the newest boats superior to the older boats, and bringing new customers into sailing. The creation of the water ballast system, described below, was a major step in creating a whole new market for our boats.

CREATION OF THE WATER BALLAST SYSTEMS

After MacGregor built tens of thousands of retracting keel sailboats, cars became smaller and lighter. Weight reduction became essential for safer and easier trailering. We then invented the water ballast system eliminating the heavy keel and providing the stability of a true keelboat. I provided the light weight needed for trailering and high performance. Take a look at the attached MacGregor 26M brochure that describes how the water ballast system works.

The light weight then allowed us to develop a high performance sailboat that can be driven at high speed by relatively low horsepower outboard motors. The culmination of all of this is the MacGregor 26M. It was a smash success.

THE BUSINESS WAS A FAMILY PROJECT.

My youngest daughter married one of my department managers. My older daughter married a guy really immersed in the marine industry, and they managed the MacGregor 65 production for many years. Over an 8 year period, they built 100 of these magnificent yachts. During it's production run, it was the best selling large yacht in the history of sailing.

My wife Mary Lou managed the office and managed all of the financial work. She had a strong and equal voice in all of the decisions and actions that were taken by the company. She was the one most responsible for buying the property and building the buildings that we now have. She was also very strong and effective critic of designs and business decisions. She effectively talked me out of doing many really dumb things that I might’ve done.

My kids sailed with me on many of the long races deep into Mexico. We have a lot of fun, and created some really hot sailors.

Sail Magazine recognized MacGregor as one of the most innovative of the sailboat builders over the last 3 decades, and as the builder that brought affordable sailing to thousands.

It has been a long and hugely successful run. We enjoyed the whole thing immensely, but it is good to be retired from the boat business. Our new career as landlords has also been a great success, and every day we give thanks that we decided to build the large boatbuilding facility that could easily be converted to industrial rentals.

Roger MacGregor